This world is but a canvas to our imagination - Henry David Thoreau

|

| Le Menec Alignment |

I saw the Carnac standing stones about 15 years ago with my friend Rob. I remember him standing staring, trying to feel his way into the thinking of people who would set up thousands of big stones into long rows. The picture above shows just a few of the stones in the Alignments there in Carnac, France. Long rows side by side, they march with little regard to terrain across the countryside by the hundreds and thousands, kilometers of them, some damaged, some missing, but principally still in place over 5,000 years after being raised.

They puzzle the mind. What did they mean, when they meant something?

By 5,700 years ago (or so) the farming peoples who came to the Carnac area had cleared the land, ploughed the soil, planted wheat. They began raising these stones, called menhirs. They moved them across the landscape and set them up without the wheel, without engineers, without geometry. Mainly they made lines, and sometimes circles, ovals, and rectangles. In addition they made graves lined with slabs of stone and covered with soil and grasses. They didn't build stone houses. They did what they did for a couple thousand years, approximately, and then they stopped.

|

| Photo credit: Wikipedia, Yolan Chériaux |

The stones are big, very heavy, and we can assume it took tremendous cooperative energy over many years to dig out, transport, and set them up. Many people have speculated about them, and Wikipedia and other internet sites give a lot of information about them. A new book on the topic is La Revolution Neolithique en France, edited by Jean-Paul Demoule, 2014. In English, we found The Carnac Alignments: Neolithic Temples, by Jean-Pierre Mohen, 2011 (2000).

Who, what, where, when, and how can be addressed with archaeology and careful reasoning. But in looking at the stones, and in looking at what's been written about them, the "Why" escapes us. Most efforts at understanding focus on presumed religious rituals. Other ideas include political power, property rights, honoring the dead, and expressions of family or clan totems. One of my friends, joking, proposed space aliens. Well.

|

| Le Menec, a set of alignments, looking west. You can see that some lines are broken. The house and barn show you where the missing stones went. |

|

| Alignments of stones seen from the side. |

More than 5000 menhirs have been counted. The smallest are the size of an end-table; the largest are not really big if you are comparing with Stonehenge. Le Menec stones top out at about 9', the Kerzerho alignment stones at about 15'. Of course, it's a job to move around even a 5 ton menhir, and these can weigh 30 tons, 50 tons. But really the amazing thing is their number, and their sort of relentless progress across the landscape.

|

| Julianne and standing stones at Kerzerho |

The stones are set about equidistant from each other, measured from their centers. This surprised researchers once they noticed it. The average distance between centers, measured with some precision in the 1970s, is 2.5 yards. This has been named the "Neolithic fathom."

At last we spent some time at the Petit Menec alignment. It was our hands-down favorite. It's off the beaten track, down a one-lane road, and could be called neglected. We, however, thought it was perfect.

|

| Ink sketch from among the stones of the Petit Menec. copyright Nancy Donnelly 2015. |

There's a single parking place, marked by a trash can. You have to walk through woods on a not-very-traveled path threatening to dissolve into wild strawberry vines which are spreading everywhere among the trees. The trees are mainly slender but tall, reaching for light. The birds are singing. The little leaves are appearing in their lovely spring green. Sunshine falls through the leaves making dappled patterns on the tree trunks, the vines, the little bushes, the grass, the stones. A tiny breeze rustles the leaves.

There's a low dry-stone wall which you can navigate by sitting on it and swinging your legs over. The woods continue, and stones appear in lines. The stones are not very big, and the lines are not complete, and not exactly straight. They march along, make a dog-leg right and continue some distance, then stop. We sat on the wall, picking a place with few mosses. We had our sandwiches and our white wine. I think I had some vegetable. Julianne was tired and stayed put, while I walked into the woods among the stones and sat to draw.

The underbrush at the Petit Menec stays small because of the shade, and the stones are full of mosses. It's quite moist here, even marshy in one place, and beautifully dim. My paper was smaller than I wished (6x12), and I was sitting on a rock. It's always something, isn't it?

The alignments are not the only way Neolithic people used big stones. That day we went to the Petit Menec, I also visited Le Manio, the largest still standing stone, about 21' tall, and off by itself though close to a rectangular enclosure of small stones.

|

| Le Manio, 21' tall. It stands alone, but in line with the eastern set, the Kerlescan, and close to a rectangular enclosure of stones. |

|

| Grand Menhir Brise, |

Here's a picture of a dolmen right in the middle of Carnac. It has been appropriated to religion with the cross on top, but that's relatively new.

|

| Dolmen among houses in Carnac, with me. Credit: photo by Julianne Duncan |

This is a tomb. There are many of them, constructed like houses with vertical slabs of stone topped by flat slab roofs, then covered with rocks and soil until they were grassy mounds. Bodies were buried within. These are called dolmens if they are small, and cairns if they are big multi-family affairs.

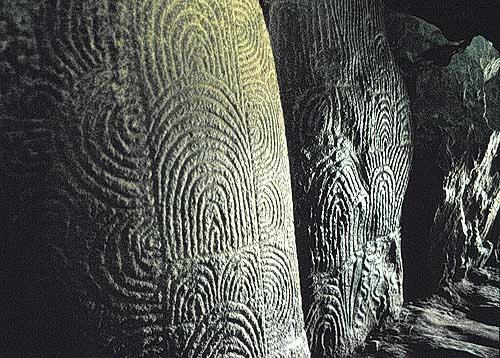

Over the centuries the smaller ones especially were revealed by erosion. Cairns yielded skeletons, jewelry, stone weapons and tools, bowls and grinders, now in the museum at Carnac, but the exposed dolmens were found empty. Here's a fast sketch I made of the cairn at Gavrinis. I would have taken a photo, but they take away your camera and everything hard or floppy during the visit. It's true the space is very narrow and low, and something like a camera swinging could chip the stone. The slab walls are covered with symbols presumed to represent human figures among other things.

|

| Entrance to Gavrinis cairn. copyright Nancy Donnelly 2015 |

|

| Carving on dolmen stones inside Gavrinis, thought to represent human forms Credit: knowth.com via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Carvings of stone knives and other shapes, Gavrinis. Credit: visoterra.com |

It's not hard to figure out what the cairns and dolmens were used for, and we can easily understand evidence of hierarchy, long-distance trade and the excellent skill in making these artifacts. These people were more sophisticated than we gave them credit for, at first.

But understanding the standing stones is not very easy. They present an enigma; the aesthetic escapes us. They're lumpy, hardly ever have carving on them, and are not very similar to one another in size. Sometimes there's a run of big ones, and sometimes there's a run of smaller ones. Otherwise, there might have been rules or principles for choosing suitable stones, but we can't make them out. They seem like humble objects, chosen by convenience.

In an odd way, they don't even seem like the point. Maybe something else was the goal.

I'm going to hazard a different guess. Perhaps admiration attached to the skill in moving and raising these outrageously heavy objects. Perhaps the stone-raising itself was a statement of prowess, and the actual stone had no further use. Maybe that's why the peoples in the area of Carnac had to keep raising more and more of them.

Maybe it was a sort of sport. A competition defining who was strongest and most clever. At Carnac we might be looking mainly at expressions of strength, hierarchy, pride, and competition.

This is likely a heretical view. Modern people search for meaning everywhere. The idea that the meaning of the alignments is transitory and has to be established over and over, constantly renewed, isn't in line with other people's ideas. I'll stick with it until a more convincing argument comes along. I'm open to a better argument.

by Nancy, also photos unless otherwise cited

No comments:

Post a Comment