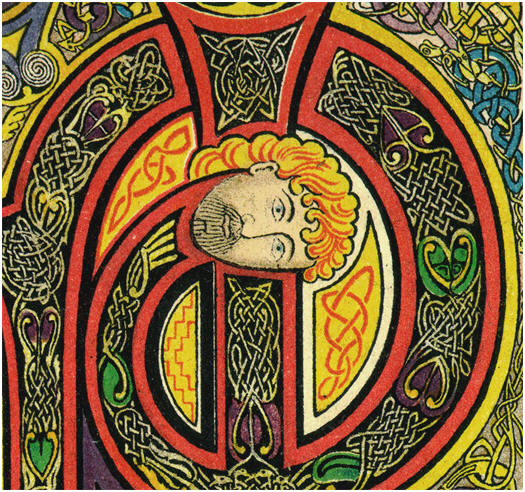

Gold, bronze, silver. Ceramic. The written word. Grand items laid our for our viewing pleasure at the National Museum of Ireland and at Trinity College, Dublin. These are not very large venues but so filled with exceptional items that we had to visit several times during our stay in Dublin, our last Irish stop. We appreciated the excellent displays and layout too. Seeing so many beautiful items in one place leads me to a reflection on Irish art through the ages as I have been seeing it these last few months. Finally seeing the Book of Kells (above) with time to appreciate the beauty and skill of the manuscript--priceless.

For us, it was fun to find the treasures from the areas we have visited. Kind of like finding an old friend to see the real Celtic golden neck ring after seeing the reproduction in the Burren Museum in Kilfenora.

For us, it was fun to find the treasures from the areas we have visited. Kind of like finding an old friend to see the real Celtic golden neck ring after seeing the reproduction in the Burren Museum in Kilfenora.The National Museum also has a full size reproduction of the church door from Dysert O'Dea church which was active from the 700's to the Cromwell era.. We feel like it was sort of our secret church since it was actually hard to find, we were totally alone out there in the cold and rain and we came upon the carvings suddenly. We felt like jungle explorers who looked up and saw the beauty of the church; thus, glad to see the reproduction of the doorway again in Dublin.

|

| Dysert O'Dea Church near Corofin, southern edge of Burren |

We also found treasures from New Grange where we had poked around and had gone inside the graves. The real Book of Kells is in Dublin but we had the pleasure of wandering what is left of the monastery in Kells town.

Keeping Dublin for last turned out to be a good idea. The museum cannot and does not try to show the megaliths, church and monastery ruins, ancient graves. We have poked around all those things to our heart's content and now could see the small treasures associated with the sites.

Why here and why now?

Always my constant question as we wander. It does become clear that there are places which have exceptional visual or other arts during some times compared with the same place at other times or compared with other places at the same time. (Did I really write this sentence? Can my meaning become clear? Sigh!) What about Ireland? Artistic high points? When and where?

Upon reflection, I see two eras which are high points for me with much other supporting fine art and architecture from other times. I am sure there are actual art experts and scholars who have refined ideas about this and maybe I will get to them. But from wandering and looking at lots of ruins and artifacts, this is what I am thinking now.

Neolithic Era and Early Medieval Ireland-High points of aesthetics and skill

The New Grange complex from about 6000 years ago (neolithic or stone age) appears to me to be an artistic high point for Ireland but also for the whole western European stone age period. Later, but with artistic continuities, the Celtic people of the early middle ages (about 600-900) produced metalwork, buildings and manuscripts such as the Book of Kells. These periods show skill and refinement of technique as well as an aesthetic sense that thrills my heart. I particularly enjoy these periods but the times before and after show artistic continuity; the museums and historic sites have fine examples of work from all periods.

Neolithic--New Grange Complex

New Grange is the overall name for a large area which includes New Grange itself, Knowth (both open to visitors) and about 40 other monuments and stone circles. The whole complex is magnificent for its engineering and social complexity. Passages to the center are built so that light enters at the solstices or equinoxes, for example. But I am stunned by the visuals which seem unmatched by their contemporaries in the Neolithic world. I will have a chance to look at more sites in Scotland, Wales and England. We got good looks at the related megalithic complexes in Brittany. Nothing else has the sheer number of carved stones as part of the grave and ceremonial sites. Locmariaquer in France is the only other site with carved stones that we have seen, in fact. I will miss the relatively new discoveries at the Ness of Brodgar in Orkney so it seems clear I will have other travels in the future to check my current conclusions But the aesthetic thrill of New Grange will always remain.

When we entered Brittany in France, we artistically left the Roman empire, the Renaissance, Baroque and dropped back in time to the Neolithic era--Stonehenge and its predecessors. Many sites in the area around Carnac have incredible stone structures. Upon arriving in Ireland, the stone monuments are both related and different. The builders of the complex structures across much of western Europe clearly shared aspects of culture. The miles of aligned standing stones in Carnac are seen no where else. However, the complexity of engineering and the artistic care taken at the New Grange Complex in Ireland seems to me like the high point of accomplishment of the neolithic farming peoples who moved into Ireland about 6-7,000 years ago from origins in the middle east.

Not only does the New Grange complex have a lot of carving, it is beautiful. Large stones--4 feet by 5 feet or so--have compositions of spirals, circles and lines which exhibit balance in composition. A clear aesthetic sensibility was at work. Beauty was clearly valued. Around the outside of the main structure are 27 carved stones which have remained in place since originally put there. Restoration has made them visible but they remain as placed millennia ago.

All the above are from Knowth and New Grange

For comparison, I am including the following are web images for Gavrinis tomb in Brittany, France, on an island near Locmariaquer. In order to protect the inside of the tomb where the carvings are, we had to check our bags and could not carry cameras. The following photos are from French Government sources.

|

| Outside of tomb. It remained unfinished. |

I do not know if the stones at either site were originally painted. At New Grange there is evidence of effort to use black and white stones for aesthetic purposes although it is not known how they were placed. The current reconstruction efforts at the two restored graves are not that successful. One related site in Spain shows some megalithic carvings with traces of paint so maybe more will eventually be known about use of color in such carvings. (Maybe we will get to see it when we get back to Spain next fall. Not sure it is open to the public.)

The recent discoveries in Orkney of the Ness of Brodgar Ceremonial complex is giving scholars new ways of thinking about the neolithic. It appears that painting and carving were used there and dating gives a very early time frame. When that site is better understood, more light may be shed on New Grange as well as the sites are roughly contemporary.

But, in my observation, New Grange complex shows a height of artistic achievement for the whole European neolithic. It was so exciting to be there after the also magnificent stone alignments and other structures at Carnac in Brittany. Stonehenge is modest by comparison and much later but is stunning for the sheer size of the standing stones. New Grange has standing stones around the main structure but they are dwarfed by those at Stonehenge and dwarfed also by the New Grange grave/ceremonial structure itself. Visiting these and other neolithic sites gives a strong sense of the sophistication of the societies. Seeing them spread across so much of western Europe highlights the communication and travel that must have been happening 5-7,000 years ago.

Trade in beautiful jade axes connects the Breton sites with New Grange and with other Neolithic sites in western Europe. The raw material for these axe heads comes from the Italian Dolomite mountains. They were never used for work and are thought to be a high status trade item. The long ones are about 8-10" long. I found them so lovely that I kept returning to look at them in both museums.

|

| Jade Axes in National Museum In Dublin, found in the New Grange area. |

|

| Jade axes from French museum in Carnac, Brittany |

The bronze age and early iron ages in Ireland show increasing skill in use of materials and building. It seems that there was a climate cooling as western Europe entered the bronze age so in Ireland, population diminished, society became less complex, more local. For example, the Burren area in county Clare where we did much of our poking around was largely uninhabited during the bronze and early iron ages (2500 BC to 300 AD more or less.) Other places were inhabited but showed less complexity of society. On the other hand a major technological revolution had taken place; metal implements made hunting and farming more productive. Technology and skill took leaps in ceramics--see my favorite jar (below) from about 2500 BC.

Having metal tools, makes such a difference artistically. The bronze age artifacts alone are stunning. These photos are of bronze age artifacts--about 2500 BC. The bronze tools were found all together in a "hoard" dug up from a bog. The ceramic jar was from a burial site in Co. Mayo.

The iron age means the entry to Ireland of the Celtic people who were also spreading all around western Europe. Around 6-500 BC they were devastating northern Italy as we saw when we visited the National Museum at Adria, Italy. Link to our earlier blog post about Adria here. The Celtic people entered Ireland around 400 BC. There appears little evidence of warfare in the early days so the assumption is that there was a mixing of old and new populations. These guys were excellent metal smiths and the technology of the farmers in Ireland really took off. Iron plows, animal harnesses and similar implements abound. However, it seems that they continued to use bronze for much of their decorative work.

This disk is about 15" across and from about 300 BC. The motif in the center is common from New Grange through the Medieval period.

This disk is about 15" across and from about 300 BC. The motif in the center is common from New Grange through the Medieval period.Christian Medieval Art

The other period of Irish art which never fails to thrill me is the medieval period from about 600-900. As Germanic peoples began migration throughout western Europe, the Roman empire withdrew leaving much of Europe and England in chaos for several centuries. Ireland appears to have had a population influx of Celtic Britons who were being squeezed out of their previous homeland. Many of those same peoples migrated to Brittany which had emptied out after the demise of the Roman empire. In Ireland, farming people spread across the land. The marginal land in the Burren was again fully populated. Iron age farming and herding was more efficient and able to support the increased population.

Christianity was present in Ireland from contact with the Roman empire but increased to become the major religion after St. Patrick entered to preach and establish the church in the mid 400's. With Christianity came writing and reverence for the written word.

Artistically, the convergence of skilled artisans, increased population with more complex social structures, writing and the production of religious books led to an artistic high point. Wealth allowed leaders to employ skilled artists. Christianity set up churches and monasteries which encouraged aesthetic expression in stone carving. The monasteries were scholastic centers which were dedicated to the spread of learning including the copying of manuscripts. Religious ritual as well as secular display encouraged fine metal work. Written gospels and other parts of the Bible were produced for teaching and eventually used for reintroducing Christianity to some other areas of Europe.

It is thrilling to see the metal work and manuscripts from the period of about 600-900. While there is a continuity of motif and design from earlier eras, these reach a high point of skill and aesthetic refinement. In the National Museum and at Trinity College, the displays allow the beauty of the era to shine. Lucky us. All we have to do is show up.

|

| A page of the Book of Kells, written in about 905. |

|

| The Brooch of Tara, gold and silver, about 6" across. |

|

| Text from the Fadden More Psalter, recently found in Co. Tipperary. Written about 800. |

|

| Embossed leather cover of the Fadden More Psalter |

Viking Influence

Viking raiders began affecting Ireland about 900. Monasteries were under pressure and many manuscripts and other items were lost. Political and social structures were similarly stressed. Artistic work suffered, artisans could not maintain the previous excellence but did continue and gradually incorporated the new influence in their work. Within a couple hundred years, the Vikings began settling in towns and established trading centers. Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford were Viking ports. Viking motifs were incorporated into Irish art, especially metal work and also in some of the motifs in the ornamentation of manuscripts. After contact with the Vikings, the artisans incorporated animal heads into their twined and spiral designs but the overall style remained a continuation of the earlier work. Vikings introduced silver so Irish art began to use combination of gold and silver.

This bishop's crook shows the use of silver but with continuity of motif. From about 1050 after Vikings had settled and had begun to integrate with the local populations.

This bishop's crook shows the use of silver but with continuity of motif. From about 1050 after Vikings had settled and had begun to integrate with the local populations.As Europe began to recover and establish cities and trading networks, Ireland was also drawn into the Medieval world. The British-Normans entered Ireland and successfully colonized most of the country. They brought the Roman church which eventually replaced the earlier rituals and governance of the Irish church. Cistercian and other European religious orders entered and the Gothic building style began to be used for churches and other public buildings. Artistic styles reflected the changes. Earlier religious items such as bells and gospels were revered and encased in decorated shrines. See our earlier blog about St. Conan's Bell to see the original bell with a Viking style handle and a Norman case. New churches were built in this period and existing churches redecorated. It is common to find stone churches from earlier periods with a Gothic style door or window as though the church leaders were wanting to adopt some of the new modern style without actually rebuilding the whole church.

The top photo is the Church of Ireland in Galway. Originally built by the Normans they used gothic arches for the structure when they created their city of Galway. It was re-purposed as a Protestant Church after Cromwell. It remains in use today and hosts traditional Irish music weekly.

The next two photos show one of the very oldest stone churches,Temple Cronin in the Burren in Co. Clare. It can be dated to the 800's by the window which is narrower at the top but there was a monastic community there from the 500's. It continued in use and has a gothic style window added later. Its interesting carvings are so weathered that I could not capture them. The church was destroyed under Cromwell and is deserted since then.

These two photos are carved detail on Temple Cronin.

Here also are some shots from Corcomroe Abbey, which was established about the same time as the church in Galway--1100-1200. It was built in the Gothic style by Benedictines who introduced Roman-style Christianity to Ireland, replacing the earlier Irish/Celtic church. Also destroyed under Cromwell but not re-purposed like the Galway church.

|

| Corcomroe with me, contemplating Irish art. |

The last specifically Irish art

This Cross of Cong is from the 12th C, shortly before the Norman-British entry into Ireland. It is one of the latest items of the "Irish" style in the museum. It is about 2-3 feet high and originally contained a relic of the true cross in the center crystal. I enjoyed spending quite a bit of time looking at the gold,silver scroll work with animal heads and much curvilinear design.

For comparison of style continuity, the photos below are from a cross of the 5th century. It is about 2 feet high.

Little evidence of renaissance, baroque in Ireland

By the time the Renaissance began to spread from Italy to western Europe, Ireland was mired in the religious and governance conflicts of the Protestant reformation in England. Henry VIII and Cromwell made great efforts to subdue the unruly island. Thus, artistic expression was limited with music and literary arts going underground, some religious artifacts going into hiding as did the Bell of St. Conan. As the Republic was formed in the mid-20th C, efforts at artistic revitalization have taken root. Crafts, dance, music and other arts appear to be thriving with emphasis on returning to Celtic roots. But that story is too complex for me to reflect on in this little blog; it could be a story for another day.

|

| Medieval cross still in place in Kilfenora, Co. Clare. Previously a monastery, now a pasture. |

Photos by Julianne and Nancy,

except the French government photos of Gavrinis.

No comments:

Post a Comment